LWLA proudly counts Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery among its long-term clients. At an impressive 478-acres, Green-Wood actively assesses the ecological implications of its landscape management practices, along with challenges brought by climate change, from more intense storms to longer, hotter periods of drought. In stewarding both urban habitat and a memorial landscape, Green-Wood seeks to mitigate and adapt to these changes. Starting in 2017, Green-Wood began reducing the frequency of turf mowing in select areas while also experimenting with less resource intensive alternatives to turf. LWLA’s Chapel Meadow, located on a steep hillside near the cemetery’s entrance, represents one such project.

Amidst the Chapel Meadow’s large mausoleums and monuments, the upland native meadow plant communities of eastern North America—typically three to four feet in height—work well. Yet this same meadow community would obscure shorter monuments common over much of Green-Wood’s landscape.

So, what meadow typologies can be economically implemented at scale and are suitable to a memorial landscape? Short-grass prairie communities, adapted to the low precipitation regimes of western North America, are not viable in our temperate region. Low growing fine fescues marketed as “low mow” alternatives to turf consist of exotic cool season species that brown out in the summer without irrigation; these species also do not offer pollinator forage and the other ecological benefits Green-Wood seeks.

Green-Wood thus faces an interesting design challenge: what meadow species native to our region remain below 15” in height—or can tolerate periodic mowing—and can be reliably and economically seeded over many acres? Starting in early 2022, LWLA began working with Green-Wood to explore solutions through a multi-year study focused on four lines of inquiry:

- What native forbs and graminoids suitable to Green-Wood remain below 15”?

- What seasonal mowing regimes keep taller native forbs and graminoids below 15” in height?

- Which taller native forbs and graminoids best tolerate seasonal mowing?

- Do high or low diversity wildflower mixes achieve higher aesthetic ratings in this context?

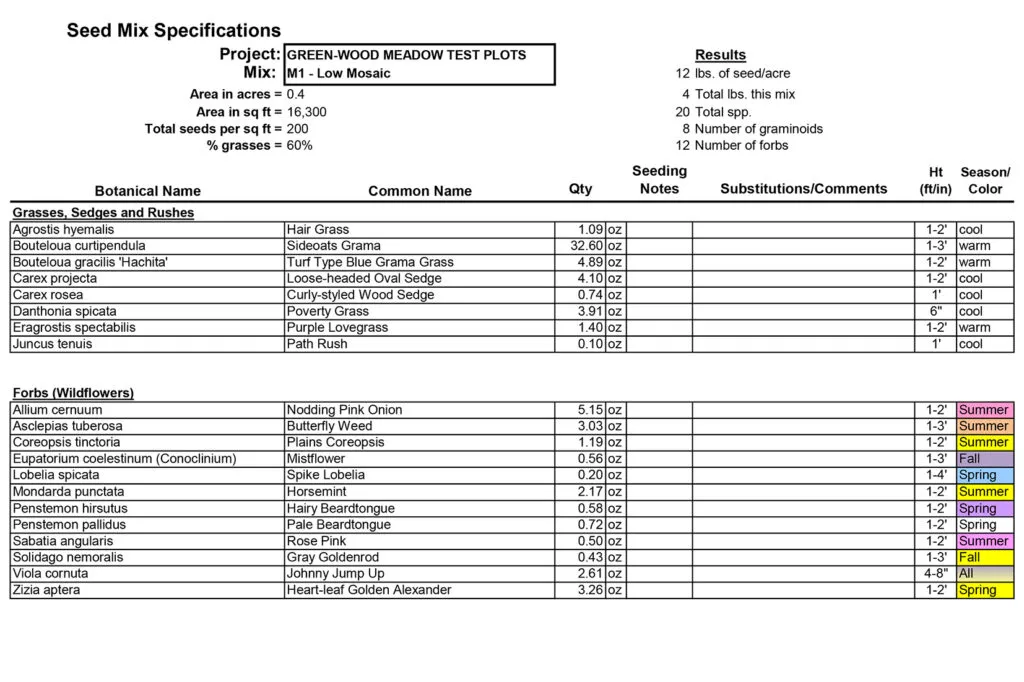

To answer these questions, the project features three seed mixes: one that we refer to as a holy grail mix in which all species are below 15” in height (excluding flowers on “see-through” stems), and two mixes that have low or high diversity of taller wildflower species. The three mixes are tested in eighteen plots subject to either no mowing during the growing season or 1-2 mowings in late spring through mid-summer to keep vegetation below 15”. All plots receive a dormant-season mow in late winter or early spring.

Commonly, test plot projects involve square or rectangular plots laid out on a grid. This approach, while useful, is not without drawbacks. Depending on plot size, plots may have a high ratio of edge area to interior, resulting in significant pressure from plot adjacent vegetation, in Green-Wood’s case clonal turf grasses and weeds. In these instances, distinguishing overall mix performance from the influences of plot adjacent vegetation can prove difficult. Assessing mix appearance in smaller plots can also be challenging: a small, seeded plot may not have the same legibility as a larger seeded area.

To avoid these drawbacks, LWLA developed a plan in which eighteen 12×12’ plots are divided across six units, with two units per mix, covering 1.3-acres in all. Embedding the plots within larger seeded units helps reduce the effect of edge vegetation. These larger seeded units—ranging from 6,400 to 11,360 square feet—also capture the visual character of a given mix better than a 12×12’ plot can. Understanding the look and feel of seeded vegetation at the site scale is especially important in a high-profile public landscape like Green-Wood.

For this study, Green-Wood selected one of its public lots near the cemetery’s entrance. Dense with low monuments across a low hill, the area offers high visibility as well as a range of conditions, from roadside embankments to south, east, and west facing slopes, and full sun to partial shade. The area is also still used for burials, meaning that the project can test in real time how mixes respond to the disturbance typical of a burial.

During the 2022 growing season, existing broadleaf weeds and turf grasses, including Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), were treated in preparation for a dormant seeding in December. Due to the density of monuments, walk-behind equipment and hand rakes were used to scarify the soil, and seed was hand broadcast. Jute matting and filter sock were placed along roadside embankments and steeper slopes to prevent erosion while seeded vegetation became established.

Establishing landscapes from seed necessarily involves unknowns. In early summer 2023, in the meadow’s first season, Canada Toadflax (Nuttalanthus canadensis), a native annual/biennial, emerged in two units. Although we often wish we could use Toadflax in our mixes, unfortunately it is often rarely available from seed houses at the scale needed. Yet somehow it ended up as a welcome “contaminant” here. While Toadflax is not anticipated to affect study findings or persist long-term given the site’s richer soils, the cheery lavender flowers bobbing in the June breeze proved lovely while present.

A seeded native meadow consisting of several dozen species does not develop uniformly like turf. Short-lived species emerge and grow more quickly than longer-lived species. Bare patches can be common, but these gaps fill in over time. Flowering is still fairly limited by early June of the first year.

Inevitably, some weed emergence is expected but is not an issue assuming proper management. Most weeds can be cut back (rather than pulled, which can lead to emergence of additional weeds) to prevent seed set and ensure ample light reaches meadow seedlings. Spot herbicide treatments address more pernicious weeds not controlled through cutting.

By mid-July 2023, the meadow units began to flower, with the greatest amount of flowering in full sun units, as could be expected. The high and low wildflower diversity mixes appeared relatively similar since both contain a comparable percentage of early successional species. Over time, the low wildflower diversity mix units, which have fewer wildflower species overall, will become more grass dominated, with the aesthetic implications of this captured as part of monitoring.

In just its first season, the project area proved particularly popular with birders following the avian communities drawn to the new forage opportunities. This felt fitting given that the project received partial funding from the Brooklyn Bird Club. Managing the impromptu desire paths created by the excited birders created an unanticipated challenge given that the designed paths serve as the dividers between each seeded unit. GPS data recording the perimeter of each seeded unit enables the marking paths to be restored for the course of the project.

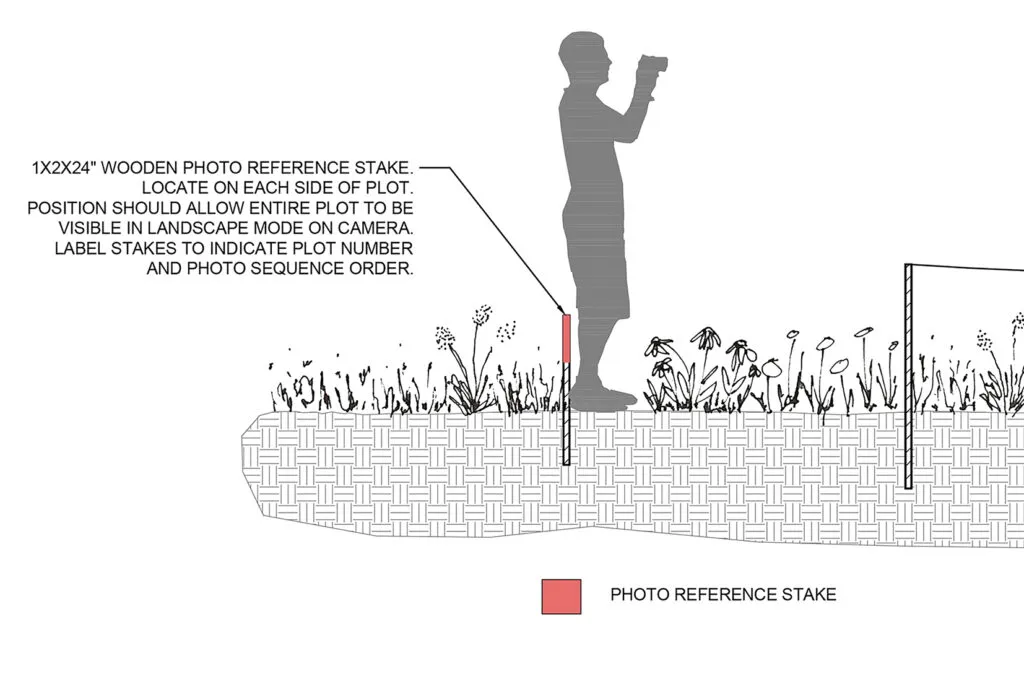

Starting in 2024, the second year of the study, using monitoring forms and photo documentation guidelines prepared by LWLA, trained volunteers will document the plots monthly and collect information about mix performance (vigor, aesthetic character, resistance to weed invasion), individual species performance, impact of mowing on individual species and vegetation overall, and vegetation height in relation to monuments. Monitoring data, while not for scientific purposes, will be score-based so that each month’s results can be quantified and compared over the course of the study.

The monitoring data from years two and three (2024-2025) will reveal how the seeded species perform at Green-Wood, including responses to mowing where required to keep vegetation below 15”. This data should also help clarify how the percentage of each species in any given mix can be refined. Yarrow (Achillea millefolium), for example, constituted 2% of the wildflowers in the high wildflower diversity mix, an amount that may be too high if a more stippled quality is desired. Making such determinations is only possible on a project like this in which mixes are compared and appearance and abundance data are collected routinely for at least several years.

Results of this study will inform the design of native meadow seed mixes and management protocols that can be scaled up for use across Green-Wood. By developing standard replicable mixes with known management regimes, costs can be reduced, an important consideration when managing hundreds of acres. Using a consistent set of proven mixes will also bring cohesion to the landscape, helping to unify the ground plane, much as turf did for cemeteries when it first began to be adopted in the 1850 and 1860s.

Applications of this study of short meadow typologies to other designed landscapes in eastern North America have yet to be considered but warrant examination, and we look forward to those opportunities. In the meantime, we commend Green-Wood for undertaking this important work. Founded in 1838, prior to Central Park, Green-Wood influenced not just cemeteries but the development of urban parks and green spaces throughout the United States, and it continues to be a leader today. We are honored to partner with Green-Wood on this work and are excited about all that can be learned from this study into what may prove to be a new kind of short native meadow for designed landscapes.